Biomes or Bust

Differences in climate around the globe make for a huge array of different types of ecosystems that support diverse sets of plants and animals. Terrestrial regions characterized by similar climate, soil, plants, and animals are called biomes. I have an idea! We could take a sailing trip, following the various ocean currents and wind patterns we’ve just talked about, stopping along the way to visit and explore all the different biomes. Let’s go!

Before we embark, let’s go over our ports of call and itinerary for the next several months. We begin our voyage in Boston Harbor, traveling south along the coast of the US to Key West. It is here that we will see the last US soil for several months. Do you have your passport? Our next port of call will be Puerto Limon, Costa Rica, then through the Panama Canal, down the South American coast to Lima, Peru.

Before we embark, let’s go over our ports of call and itinerary for the next several months. We begin our voyage in Boston Harbor, traveling south along the coast of the US to Key West. It is here that we will see the last US soil for several months. Do you have your passport? Our next port of call will be Puerto Limon, Costa Rica, then through the Panama Canal, down the South American coast to Lima, Peru.

From Lima we will take a trek to the Andes mountains and see Machu Picchu. After returning to Lima, we will travel further south to Concepcion, Chile. After leaving port in Chile, we will travel against the southern currents until we pick up the east Australian current and make landfall in Brisbane, Australia. We will sail around the southernmost point of Australia and follow the south equatorial current to Cape Town, South Africa. Once rested, we will begin our northern route to Walvis Bay, Namibia, and Luanda, Angola. We will then travel up the African coast, heading for the port cities in Portugal and Ireland, with only short stops in those places. We will then sail onward to Reykjavik, Iceland, Nuuk, Greenland, and then to the island of Newfoundland, our last foreign port of call. We will return to Boston after 9 months of traveling, documenting all we can about the biomes we encounter. I am excited that you are here to join me on this voyage, so now, let’s finally set sail.

As we travel out of Boston Harbor, it is a rainy spring day. We stay close to shore, avoiding thunderstorms, and begin documenting our first biome, the temperate deciduous forest. These biomes are classified as having moderate annual temperatures with long warm summers and cold winters. There is an abundance of precipitation, and as a result, many broad leaved deciduous trees grow here. New England, of course, is famous for its fall foliage from the maple, oak, hickory and poplar trees. It is spring, however, so we begin to see the buds on the trees as the forest comes to life with small mammals such as squirrels, rabbits, mice, and many migratory birds who have just returned from their winter habitats..

As we travel out of Boston Harbor, it is a rainy spring day. We stay close to shore, avoiding thunderstorms, and begin documenting our first biome, the temperate deciduous forest. These biomes are classified as having moderate annual temperatures with long warm summers and cold winters. There is an abundance of precipitation, and as a result, many broad leaved deciduous trees grow here. New England, of course, is famous for its fall foliage from the maple, oak, hickory and poplar trees. It is spring, however, so we begin to see the buds on the trees as the forest comes to life with small mammals such as squirrels, rabbits, mice, and many migratory birds who have just returned from their winter habitats..

It has now been several days and we are finally at our last US port of call, Key West, Florida. It is here that we will restock and make sure we have all the necessary documents to make our travels south to Costa Rica. Although Key West is not a tropical rainforest, its humidity is getting to me, even on this spring day. Well, we have a long journey ahead. Let’s go.

It has now been several days and we are finally at our last US port of call, Key West, Florida. It is here that we will restock and make sure we have all the necessary documents to make our travels south to Costa Rica. Although Key West is not a tropical rainforest, its humidity is getting to me, even on this spring day. Well, we have a long journey ahead. Let’s go.

Hola! We are now in Puerto Limon, Costa Rica, home to some of the most beautiful rainforests in the world. Rainforests like those in Central and South America are centered around the equator, where hot moist air facilitates frequent rainfall and warm temperatures year round. There are so many plants and animals in the rainforest, I am not sure how we can document them all. In fact, it is thought that there are still hundreds if not thousands of organisms that remain unidentified in these forests. It is said that the tropical rainforests have one of the highest levels of primary productivity and biodiversity of all the biomes. Tropical rainforests are dominated by broad leaf plants which maintain their leaves year round. The forest floor is often dark since the canopy blocks much of the sunlight. Many plants as well as animals live in the forest canopy as well as the forest floor, creating many microhabitats within this biome. Check out this footage of a leaf frog I just got!

Hola! We are now in Puerto Limon, Costa Rica, home to some of the most beautiful rainforests in the world. Rainforests like those in Central and South America are centered around the equator, where hot moist air facilitates frequent rainfall and warm temperatures year round. There are so many plants and animals in the rainforest, I am not sure how we can document them all. In fact, it is thought that there are still hundreds if not thousands of organisms that remain unidentified in these forests. It is said that the tropical rainforests have one of the highest levels of primary productivity and biodiversity of all the biomes. Tropical rainforests are dominated by broad leaf plants which maintain their leaves year round. The forest floor is often dark since the canopy blocks much of the sunlight. Many plants as well as animals live in the forest canopy as well as the forest floor, creating many microhabitats within this biome. Check out this footage of a leaf frog I just got!

It was hard to leave the lush rainforest of Costa Rica, but we must get through the Panama Canal before the rush of boats comes in the summer. We get glimpses of the rainforest as well as tropical dry forests while traveling through Panama, but we have set our compass towards Lima, Peru.

It was hard to leave the lush rainforest of Costa Rica, but we must get through the Panama Canal before the rush of boats comes in the summer. We get glimpses of the rainforest as well as tropical dry forests while traveling through Panama, but we have set our compass towards Lima, Peru.

As we travel down the western coast of South America, we see off in the distance the impressive peaks of the Andes Mountains. This is our next stop on our journey. We dock our boat in Lima and head up to Cuzco, Peru. Our goal: Machu Picchu, deep in the Andes mountains. Along our way, we are noting all the important aspects of the mountain biomes, including cooling temperatures and vegetation changing with elevation. Deciduous trees give way to coniferous trees, then ever so slightly to tundra. Although we will be visiting these biomes on other legs of our trip, we note the change of animal and plant species along our route. The dramatic changes in slope, climate, soil and especially oxygen are finally getting to me as we reach ice-capped mountain tops and glaciers. The water storage here is amazing, and we take many photographs and videos. We finally reach our goal, Macchu Picchu, and it was well worth the climb.

As we travel down the western coast of South America, we see off in the distance the impressive peaks of the Andes Mountains. This is our next stop on our journey. We dock our boat in Lima and head up to Cuzco, Peru. Our goal: Machu Picchu, deep in the Andes mountains. Along our way, we are noting all the important aspects of the mountain biomes, including cooling temperatures and vegetation changing with elevation. Deciduous trees give way to coniferous trees, then ever so slightly to tundra. Although we will be visiting these biomes on other legs of our trip, we note the change of animal and plant species along our route. The dramatic changes in slope, climate, soil and especially oxygen are finally getting to me as we reach ice-capped mountain tops and glaciers. The water storage here is amazing, and we take many photographs and videos. We finally reach our goal, Macchu Picchu, and it was well worth the climb.

After recovering from a lack of oxygen and the adrenaline rush of the Andes mountains, we return to our little boat and head further south to Concepcion, Chile. It is here we will document another biome, known as the chaparral. Chaparrals, often found between deciduous forests and grasslands, are found in temperate regions of the world. Sometimes referred to as temperate grasslands, their proximity to the ocean gives these biomes a slightly longer rainy season and higher humidity than the nearby deserts.

After recovering from a lack of oxygen and the adrenaline rush of the Andes mountains, we return to our little boat and head further south to Concepcion, Chile. It is here we will document another biome, known as the chaparral. Chaparrals, often found between deciduous forests and grasslands, are found in temperate regions of the world. Sometimes referred to as temperate grasslands, their proximity to the ocean gives these biomes a slightly longer rainy season and higher humidity than the nearby deserts.

Dominated by low growing shrubs and trees, chaparral is prime habitat for deer, jackrabbits, lizards and many birds. The soil is thin and fragile and is often not fertile enough to grow crops. Plants in this area spread their seeds during the frequent fires and have developed fire-resistant roots to withstand the flames.

We will now begin our long voyage in open seas, leaving the coast of South America and heading against the west wind drift until we hit the east Australian current. Our compasses are set toward Brisbane, Australia, our next port of call.

G’day, mate, we hear from the docks as we make landfall and dock our boat in the marina in Brisbane. It is great to be on solid soil again. After a brief rest we will begin our walkabout to the Austrialian outback to document yet again another one of earth’s magnificent biomes.

We will now begin our long voyage in open seas, leaving the coast of South America and heading against the west wind drift until we hit the east Australian current. Our compasses are set toward Brisbane, Australia, our next port of call.

G’day, mate, we hear from the docks as we make landfall and dock our boat in the marina in Brisbane. It is great to be on solid soil again. After a brief rest we will begin our walkabout to the Austrialian outback to document yet again another one of earth’s magnificent biomes.

You cannot miss the intense sunlight and stifling heat as you head out into the desert. Home to many cacti, succulent plants and hearty animals, the desert is nearly devoid of shade trees and protection from the dry winds. Deserts can range from tropical to temperate or even cold, depending on annual precipitation and temperature. At night, deserts lose their heat quickly to the atmosphere, creating cold dry nights under a multitude of stars. The soils here are very fragile due to the lack of water and slow decomposition rates. All-terrain vehicles can damage an ecosystem like this one which is slow to recover. As the sun sets, we are careful to only walk on the marked paths of visitors before us, taking many pictures but, as they say, leaving only footprints!

Back on the boat and recharged from an invigorating walk in the desert, we are now allowing the south equatorial current to take us to the coast of Africa. Our next destination is Cape Town, South Africa.

Back on the boat and recharged from an invigorating walk in the desert, we are now allowing the south equatorial current to take us to the coast of Africa. Our next destination is Cape Town, South Africa.

After many days at sea and battling enormous waves in the Indian Ocean, we finally arrive in Cape Town. Our goal here is to view and record data about the tropical grassland savanna. Luckily, we have hooked up with a guide who will take us on an African safari to see the savanna in Kruger National Park near the Zimbabwe border. The tropical savanna in Africa has an amazing amount of animals, ranging from the herbivorous zebras, giraffes and wildebeests to their predators, namely the lions and hyenas. Water is very much seasonal, which means vegetation follows suit. With deep roots and drought-resistant seeds, plants quickly bloom then dry up during the wet seasons.

Animals gather by watering holes, eating grasses and stems, storing up the fat for the dry season ahead. The warm temperatures year round mean that our late summer/early fall safari is still subject to the intense south African sun.

We have been at sea for 6 months now, traveling from Boston through Central and South America, Australia and South Africa. As we begin our travel north, we have a few quick stops in Walvis Bay, Nambia, and Luanda, Angola, to see the tropical dry forests of western Africa. Tucked between the dry savanna, coastal wetlands and a deciduous forest to the north, the tropical dry forests have warm temperatures but less rainfall than the tropical rainforests of Costa Rica and South America. Still, these forests provide habitat to many important organisms, such as birds, bats, lizards, trees and shrubs. Many of the trees usually found here have been cut to use for building or clear land for grazing. There is also a lot of oil extraction and fossil fuel exploration in this part of the world. Although we only see this biome from along the shoreline, we document its characteristics and finally say goodbye to the Southern Hemisphere.

We have been at sea for 6 months now, traveling from Boston through Central and South America, Australia and South Africa. As we begin our travel north, we have a few quick stops in Walvis Bay, Nambia, and Luanda, Angola, to see the tropical dry forests of western Africa. Tucked between the dry savanna, coastal wetlands and a deciduous forest to the north, the tropical dry forests have warm temperatures but less rainfall than the tropical rainforests of Costa Rica and South America. Still, these forests provide habitat to many important organisms, such as birds, bats, lizards, trees and shrubs. Many of the trees usually found here have been cut to use for building or clear land for grazing. There is also a lot of oil extraction and fossil fuel exploration in this part of the world. Although we only see this biome from along the shoreline, we document its characteristics and finally say goodbye to the Southern Hemisphere.

At this point in our journey, we are starting to feel homesick. After stopping in a few European port cities in Portugal and Ireland, we quickly set our sail northward in hopes of reaching Reykjavik, Iceland, and Nuuk, Greenland, by mid fall. This journey has taken us to so many biomes, each demonstrating the diversity of life and differences in temperature and precipitation. Nothing, however, has prepared us for the harsh contrast of the Arctic tundra and polar ice in Iceland and Greenland.

At this point in our journey, we are starting to feel homesick. After stopping in a few European port cities in Portugal and Ireland, we quickly set our sail northward in hopes of reaching Reykjavik, Iceland, and Nuuk, Greenland, by mid fall. This journey has taken us to so many biomes, each demonstrating the diversity of life and differences in temperature and precipitation. Nothing, however, has prepared us for the harsh contrast of the Arctic tundra and polar ice in Iceland and Greenland.

As we dock our boats in the chilly waters of Reykjavik, Iceland, we quickly note the lack of trees and barren volcanic landscape of this island. Iceland is a geothermal hot spot, and we enjoy the hot springs which dot this country. Recalling the mountain tundra of the Andes, the Arctic tundra is similar in temperature and seasonal variations. The permafrost and surrounding soils contain lichen, mosses and other low growing plants and shrubs which grow for a short period of time during the summer, when the sun never falls below the horizon. Winters, however, are just the opposite, with only 3 to 4 hours of sunlight through the long winter months. Animals that live here are adapted to cold, harsh conditions. A layer of body fat and thick coats of fur protect them from the harsh climate. The Arctic wolf, Arctic fox, musk ox, and the endemic Icelandic horse are just some of the animals we have encountered here.

We take a day trip from Iceland over to Nuuk, Greenland, by sea plane. A rare treat away from our little sailboat, we fly over the polar ice and glaciers of this largest island in the world. With few roads and wildlife outnumbering humans, this icy landscape has is not "green" as its name implies and there is much discussion with the bush pilot as to the fate of the melting glaciers and icecaps. Animals found here, such as polar bears, ermine and hares, are adapted to yearly mean temperatures below 10 degrees Celsius. Some of the most impressive organisms found here are the whales, however, which first brought settlers to this harsh icy environment.

As we take the last dip in the geothermal hot springs of Iceland, we wave goodbye to our friends in Reykjavik and head for our final port of call, the island of Newfoundland off the coast of northeastern Canada. It is here that we will document our last biome, the coniferous forest. Dense with evergreen trees such as Douglas fir, spruce and redwoods, the coniferous forest has a low diversity of flora, since few plants have adapted to the harsh cold and dry winters. Thanks to the slow decomposition on the forest floor, the soil is highly acidic and not conducive for crops. There is, however, an abundance of wildlife as we catch glimpses of wolves, lynx, moose and even caribou swimming along their migration route alongside the boat! Despite the breathtaking scenery, we are eager to complete our voyage and return once more to Boston.

As we take the last dip in the geothermal hot springs of Iceland, we wave goodbye to our friends in Reykjavik and head for our final port of call, the island of Newfoundland off the coast of northeastern Canada. It is here that we will document our last biome, the coniferous forest. Dense with evergreen trees such as Douglas fir, spruce and redwoods, the coniferous forest has a low diversity of flora, since few plants have adapted to the harsh cold and dry winters. Thanks to the slow decomposition on the forest floor, the soil is highly acidic and not conducive for crops. There is, however, an abundance of wildlife as we catch glimpses of wolves, lynx, moose and even caribou swimming along their migration route alongside the boat! Despite the breathtaking scenery, we are eager to complete our voyage and return once more to Boston.

It has been nearly 9 months since we left Boston Harbor on our trip around the globe. We have documented data about all of the world biomes, seen rainforests and desert, encountered giraffes and whales, flown over polar icecaps and walked in the hottest of deserts. Thank you for taking this journey with me, and I hope to see you again soon on another voyage to discover the wonders of our planet earth.

It has been nearly 9 months since we left Boston Harbor on our trip around the globe. We have documented data about all of the world biomes, seen rainforests and desert, encountered giraffes and whales, flown over polar icecaps and walked in the hottest of deserts. Thank you for taking this journey with me, and I hope to see you again soon on another voyage to discover the wonders of our planet earth.

Biomes

Before you forget all that you saw and learned on your trip around the world, let’s review some of your knowledge .

Temperate Deciduous Forests

Moderate temperatures and rainfall which change with the season. Oak, maple, beech are common, slow rate of decomposition.

Tropical Rain Forests

Found near the equator, warm and wet conditions, dominated by broad leaf plants, high primary productivity.

Coniferous Forests

Coniferous Forests, also known as Taiga or Boreal Forests, are dominated by evergreen trees such as spruce, fir and cedar. Cold weather and long winters. Abundance of wildlife including deer, moose and elk.

Coniferous Forests, also known as Taiga or Boreal Forests, are dominated by evergreen trees such as spruce, fir and cedar. Cold weather and long winters. Abundance of wildlife including deer, moose and elk.

High Mountains

High mountains store water and have a steep slope, and see major changes in climate, soil, vegetation and animals over a short distance.

High mountains store water and have a steep slope, and see major changes in climate, soil, vegetation and animals over a short distance.

Chaparral

Also known as temperate grasslands or shrublands, very close to the sea so higher humidity than other grasslands and deserts. Dominated by dense low lying vegetation or shrubs, home to many birds, lizards, and fire resistant plants.

Desert

A desert as very little precipitation, temperature is hot during the day and can be cold at night due to loss of heat to the atmosphere, dominated by plants which store water like cactus and other succulents. Tropical, temperate and cold deserts exist which vary by precipitation and temperature

A desert as very little precipitation, temperature is hot during the day and can be cold at night due to loss of heat to the atmosphere, dominated by plants which store water like cactus and other succulents. Tropical, temperate and cold deserts exist which vary by precipitation and temperature

Savanna

Also known as tropical grasslands has clumps of trees such as acacia and has warm temperatures year round. Wet and dry seasons exist in this biome. Animals that make their home here include zebras, giraffes, and lions.

Polar Ice

Polar Ice caps found in Greenland and Antarctica have year round snow and ice on the ground. Temperatures rarely get above freezing and days are short and dark. Many of the ice caps are melting due to global temperature change.

Arctic Tundra

Also called cold grasslands or alpine tundra because they are near the polar ice, very cold temperatures and harsh winds, low growing plants, permafrost, long dark winters, and a fragile ecosystem.

Text Version

Lab: Understanding Productivity

Lab: Understanding Productivity

Now that you’ve explored all the fascinating biomes out there, we need a way to talk about how productive they are. The rate at which some amount of biomass can be made out of solar energy is called gross primary productivity (GPP). This rate allows us to compare productivity of different biomes. The rate at which producers use photosynthesis to produce chemical energy minus the rate at which they use some of this chemical energy for respiration is called net primary productivity (NPP). That gives you a basic definition, but the difference between GPP and NPP is often hard to get an intuitive feel for. In this lab, you will do an experiment that determines the difference between GPP and NPP in test bottles containing photosynthetic microorganisms.

Lab: Objectives

Lab: Objectives

- Distinguish between gross primary productivity (GPP) and net primary productivity (NPP).

- Identify the impact of various abiotic factors in GPP and NPP.

NOTE: Use this lab data if you are unable to do your own lab at school. If you are planning to do this lab using your own tools and data set from your own experiment, please notify your instructor.

Before we begin, make sure you have all of the following materials ready to use.

Lab: Materials

Lab: Materials

- Notebook and pencil

- Roll of Aluminum foil

- 1.5 L pond water with algae samples in it

- Pot for boiling 1.5 L of water in and access to a stove top

- Clock or watch

- Dissolved oxygen test kit

- 500 mL plastic bottles with caps (3)

- 100 mL graduated cylinder

- 500 mL beaker

- A funnel that fits the plastic bottles

- Gloves

Lab: Procedure

Lab: Procedure

For this experiment, you will need to collect two bottles full of pond water that has microorganisms in it. Often you will get microorganisms in it if you sample from areas that have algae cover.

- Take two of your plastic bottles with screw-on caps to a local pond. Fill them completely (all the way to the brim) with pond water and make sure you get some algae in the bottles. Before you seal them tightly, quickly measure the dissolved oxygen (DO) content of each bottle using your dissolved oxygen test kit, record this on your lab worksheet, and then tightly seal the bottles. There should be no air bubbles in the bottles when you seal them. Making sure they are capped tightly and that they are completely full to the brim with no air inside will ensure that your experiment is accurate.

For this experiment to work correctly, the DO level of the pond water must be at or below 4 ppm. If your water does not have a DO below 4 ppm, you can boil it for 5 minutes, then allow it to cool for approximately 30 minutes. Measure the DO again and it should be around 4 ppm. - Cover one of the bottles, including the cap, completely with aluminum foil so that no light can get in. Fill a third bottle with tap or filtered water to use as a control.

- Place the three bottles in a location where they will all get an equal amount of sunlight. On your lab worksheet, mark the time you set the bottles in the sunlight. All three should be set down at the same time and left there for 24 hours.

- After 24 hours, remove all the bottles from the light at the same time. Be careful not to jostle or shake them. Using your DO test kit, test the DO level from the middle region of the bottle. To do this, you may need to pour off some of the top water first. Record the DO level on your lab worksheet.

- Finally, clean up all your materials, and get prepared for the data analysis section of the lab.

Lab: Data Analysis

Lab: Data Analysis

In this experiment, microorganisms in one of the bottles were able to photosynthesize while in another only respiration was occurring. Click on the images below to learn what data each bottle will be able to give us.

Answer questions 3-14 on your lab worksheet. When you have completed the lab, submit your completed lab to the Lab: Understanding Productivity link for grading.

Biomes Productivity

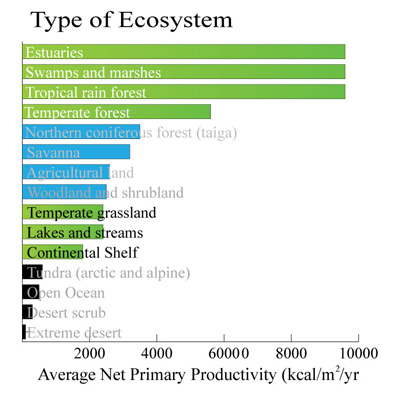

Now that you know the difference between NPP and GPP, let’s return to thinking about some of those biomes you visited earlier. Which terrestrial biomes do you think have the greatest NPP?

>

>

NPP levels are high where there are warm, moist conditions. Swamps, estuaries, marshes, and tropical rainforests all have an abundance of warm water.

Luxurious growth in tropical rain forests signals high productivity. It would be natural to assume that tropical soils are very fertile in order to support this high productivity. In fact, the soils are very thin and the rock below them highly weathered. What makes humid tropical forests so productive is the combination of high temperatures, light, and rainfall year-round coupled with especially efficient nutrient recycling. Nutrient cycling occurs so quickly here that very few nutrients are stored in the soil, making it impractical for farming and agriculture.

Take a look at the photo below. This is a cloud forest high up on the island of Borneo in Indonesia.

(source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Cloud _forest_mount_kinabalu.jpg)

Cloud forests can be seen in many places, notably Indonesia, Costa Rica, and Ecuador. They are warm and tropical, but are covered in clouds nearly all day, every day, such that every plant is covered in moisture. This makes them very productive ecosystems, on par with tropical rain forests.