The Factors of Soil Formation

Gather a handful of soil from your backyard or neighborhood.

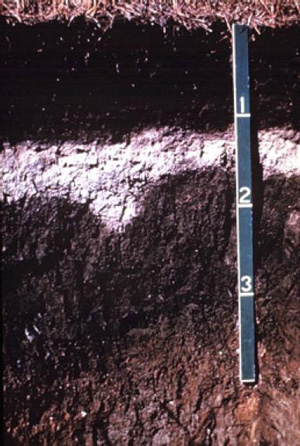

The two main components of soil (inorganic and organic) vary by climate, vegetation type, degree of weathering, and other factors. A soil that forms from the weathering of limestone in a humid environment will have very different properties from one that forms from sandstone in a cold environment. Some soils are deep and rich in nutrients, while others are shallow and relatively infertile. Most soils are somewhere in between these two extremes. In all cases, there are five factors that directly affect the quality of the soil.

Factor 1: Parent Material

Soil develops from its parent material. The parent material could have been rock that was weathered in place, or rock particles that have been transported by wind, water, ice, or gravity. Parent material is the most important soil-forming factor during the early stages of soil formation. If the parent material is coarse-grained and relatively resistant to weathering, then the soil will form slowly. The result will be course-grained soil. Quicker soil development would result in finer soil.

Soil fertility also depends on the parent material because different rocks contain different chemical elements and minerals. Some rocks contribute important nutrients to the soil while others do not. Limestone has adequate amounts of the elements, calcium and magnesium, and both of these are important plant nutrients. Sandstone, however, contains very little, if any, of these elements and weathers into a less fertile soil than limestone.

Factor 2: Climate

On a worldwide basis, soils show a very close correlation with climate. Climate determines the atmospheric conditions and the precipitation of an area, and these in turn influence weathering rates. Precipitation is especially important because it allows ions and chemicals to react with parent material and to be carried through the soil. These chemicals advance the weathering process, which changes parent material into soil. Climate also determines the vegetation in an area. The more vegetation there is, the more humus there is in the soil. Hot dry deserts have limited vegetation and limited precipitation and so they have less developed soils than temperate and tropical forest areas. Likewise, polar areas have limited bacterial activity to break down organic matter, so soils there usually have small amounts of humus.

Factor 3: Topography

Topography describes the slope of the land. It determines how quickly and easily water can roll off of the land. For good soil formation, the parent material needs to interact with water. If the slope is steep and all the water moves downhill, soil-forming processes are hindered. As slope increases, so does the amount of soil that is lost by erosion, or the carrying away of soil by running water. Thus, steeply-sloped areas usually have shallow, less developed soils than flat areas.

Factor 4: Biological activity

Organisms, big and small, play a huge role in soil formation. They add organic matter and nutrients, aid decomposition, and play a role in weathering. Every handful of soil contains millions and millions of microscopic organisms that break down dead plant and animal material, returning nutrients to the soil. On a macroscopic level, larger plants, such as trees, also influence the soil. For example, the leaves of deciduous trees, like oak and maple, contain several important soil nutrients. When the leaves decompose on the forest floor, they return those nutrients to the soil. Pine tree leaves are relatively nutrient-free. When they decay, they do not add nutrients to the soil.

Factor 5: Time

Time also plays a role in soil development. Weathering proceeds as time advances. As time goes by, most soils become deeper and more developed. Soils in warm moist areas develop faster than those in cold dry climates.