Galleria: Class Formation

American workers grew bitter over the changes brought about by increasing mechanization and the factory system. Click the galleria to learn about the increasing class tensions spawned by the industrial revolution.

-

Industrialization marked the demise of the craft shop system in which artisans could take pride in creating a product from start to finish. Instead of the American worker being self-employed, the nation was turning to wage labor. In factories, workers toiled longer hours performing repeated tasks in the assembly process. As the pay and status of manual laborers declined, salaries of managers and clerks in the non-manual sector increased.

-

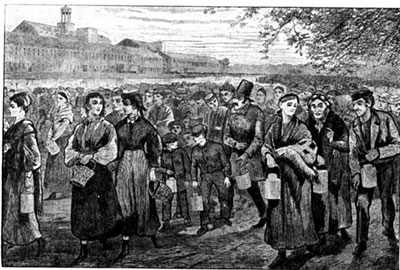

Thus, the factory system spawned a growing class consciousness as the distance between the manual and non-manual sectors widened. Women, children, and later immigrants took the lowest paying jobs. In the old days, male artisans and apprentices worked together at the same bench. In the impersonal factory, workers remained at their machines, far removed from the owners. This segregation continued outside the factory as well. Cities divided into middle class and working class neighborhoods.

-

Simmering discontent among the workers spawned early attempts at organizing into unions. Laborers went on strike, demanding shorter hours, better pay, and improved working conditions. Though they won a few victories, unions made little progress in achieving their goals in the 1830s and 1840s. Skilled workers conducted the he most successful strikes since their labor required specialized knowledge or ability. Owners frequently exploited the ethnic, religious, gender, and occupation differences among the workers to limit their gains. The growing labor pool fed by immigration further hindered labor's efforts during this period, since unskilled labor became plentiful.

-

Wealth inequalities increased along with the growth of American production. To put it another way, the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. In New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, for example, the richest one percent owned 25 percent of the total wealth in those cities in 1825. By 1850, the same one percent owned half the wealth. Similar trends occurred in St. Louis, Cincinnati, and other western cities.